Noa Taylor is an interdisciplinary artist working primarily in photography, AI, video, and installation. Taylor’s work deploys contemporary digital aesthetics and context collapses to revisit and recuperate the problematically and superficially queer representations in our collective visual media inheritance.

“We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.”

— José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia

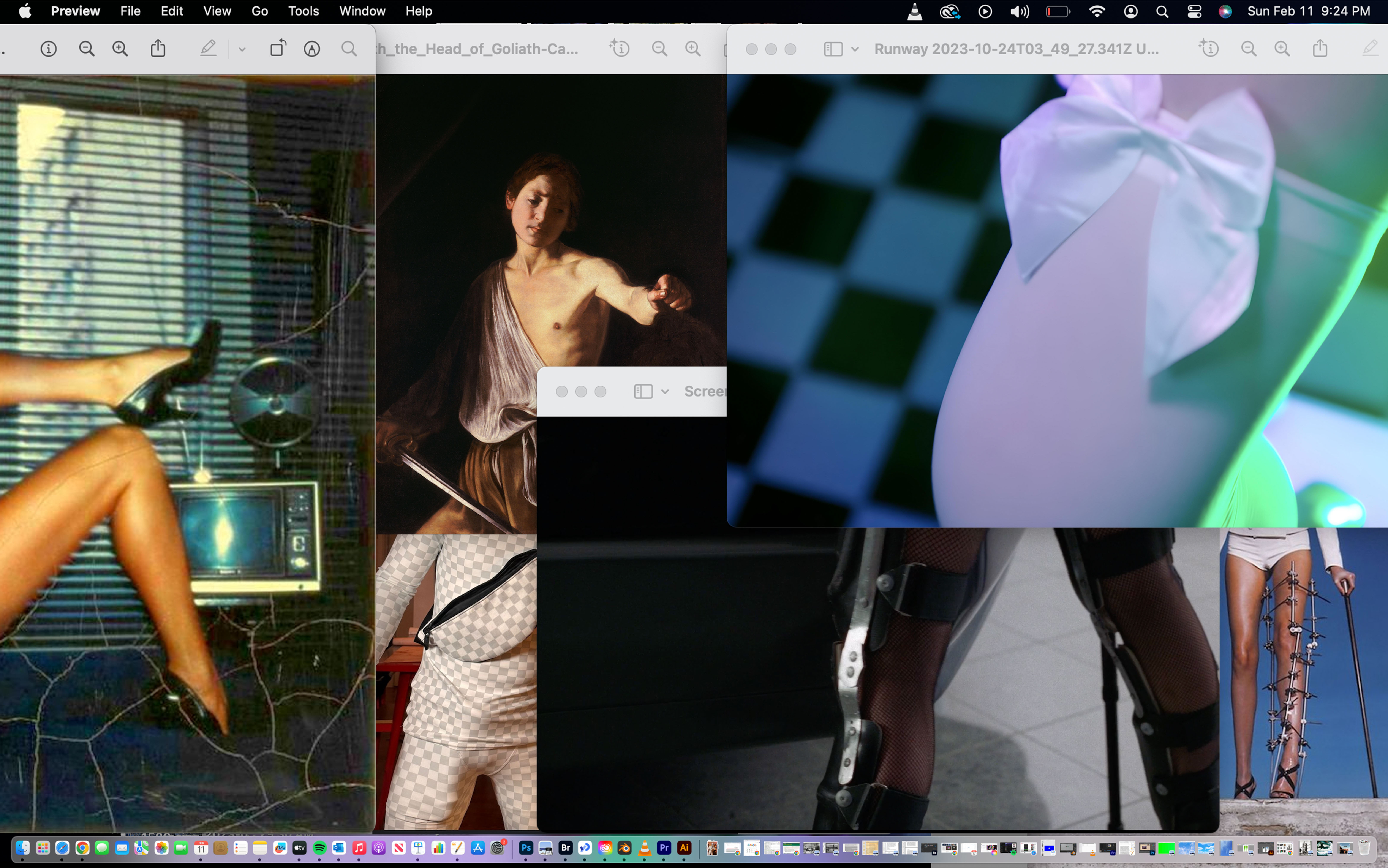

Digital autochronicity is a framework that arises from the method of image consumption and circulation on sites like Pinterest and Tumblr, both of which value formal and thematic through-lines over maintained chronology. On these sites, disparate images invite comparison simply by virtue of being viewed together; regardless of historical origin, medium, or location, reposting images in succession inscribes each with new meanings through shifting contexts. In this way, the framework of digital autochronicity is imbued with queer potential. Rather than prioritizing nostalgia, these spaces are always in motion, the past, present, and future conversing, activating each other, a subversion or queering of chronology. Horizon lines are contained in windows, interrupted by their neighbors sitting in front and behind them — a queering of perspective. Machines of Loving Grace aims to activate digital autochronicity to recuperate problematic queer representations in our cultural inheritance.

One such representation is Crash, a 1996 film directed by David Cronenberg based on the 1973 novel by J.G. Ballard. Following a group of car crash fetishists — at once a death cult and public sex/queer kink subculture — the original media is simultaneously marked by an undercurrent of queer hesitancy and the possibility for queer utopian interpretations. My own first viewing of Crash places it amongst the autochronic — a decade ago, on my phone, bouncing between apps, streaming the film through an illegal site during the wee hours of the morning. Experiencing Crash in this manner contextualized the film amongst the other content I consumed and circulated online — these context collapses are made visual through screenshot collages. Ultimately, the languages, structures, and filters of the digital became the lens through which I understood the film and its queer potential.

Crash (2024) is an AI remake the film; it is a revisiting, a recuperating, a queering of Crash through current software. Recreating Crash through AI reaches towards queer potentials because its datasets are autochronic: a grand accumulation of our collective pasts and presents, hopes and biases shuffled together, activated simultaneously. In Crash (2024), the warped visuals of AI makes bodies and machines merge, the gender expressions of figures shifting in and out of recognition and specific binary assignment. AI’s failure to render accurate bodies is a queering of representation, as the divisions between sex and gender, technology and biology, collapse.

On the one hand, as these moments of failure (glitch, kink, accident) become the expectation rather than a disruption, they reflect back on the systems that deem them erroneous. On the other hand, because of community guidelines and internal biases, there are moments in Crash (2024) that AI won’t generate. Rather than deleting these moments, or finding a work-around, the lost cuts are filled in with dead screen blue. The blue screen serves as a space holder: as an indicator of a computer crash, it archives AI’s failure within its ever evolving and ever learning progress, a gesture toward what could, would, or will be. These moments of failure are the places through which we might reach towards a recuperation of queer representations, the gaps between the cogs of our cultural inheritance where the light of something else trickles through.

www.noa-taylor.com

@noa.osric